IN THE FLESH

A WORKSHOP WITH LUCIEN CASTAING—TAYLOR

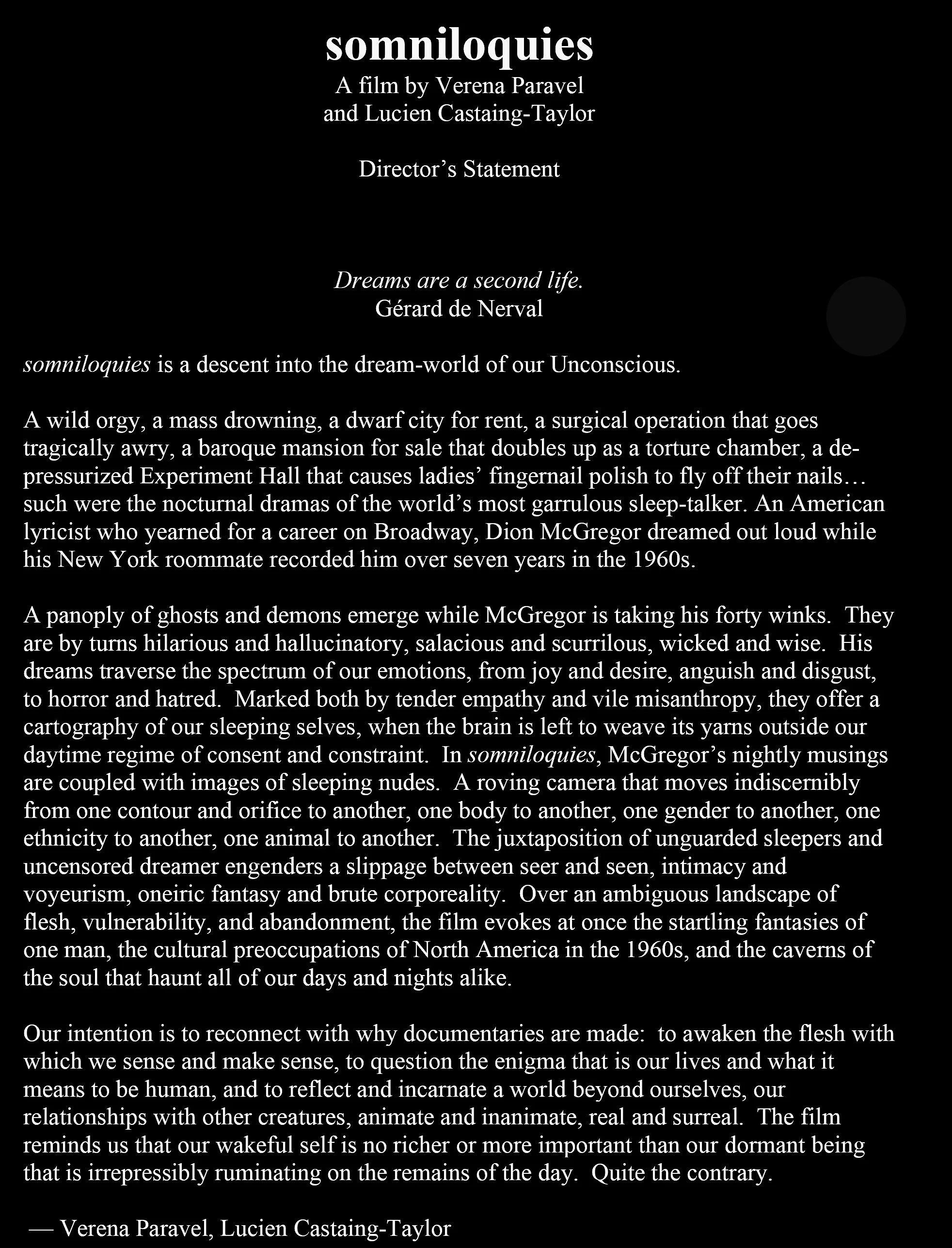

This inaugural CEMA Visiting Artist Series Workshop with anthropologist and artist Lucien Castaing-Taylor attends to the mystery, beauty and horror of the human body. It will feature a screening of the groundbreaking film SOMNILOQUIES (2017, dir. Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, 73 min.) followed by a discussion on how bodily experience and consciousness are depicted in the films DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA and SOMNILOQUIES.

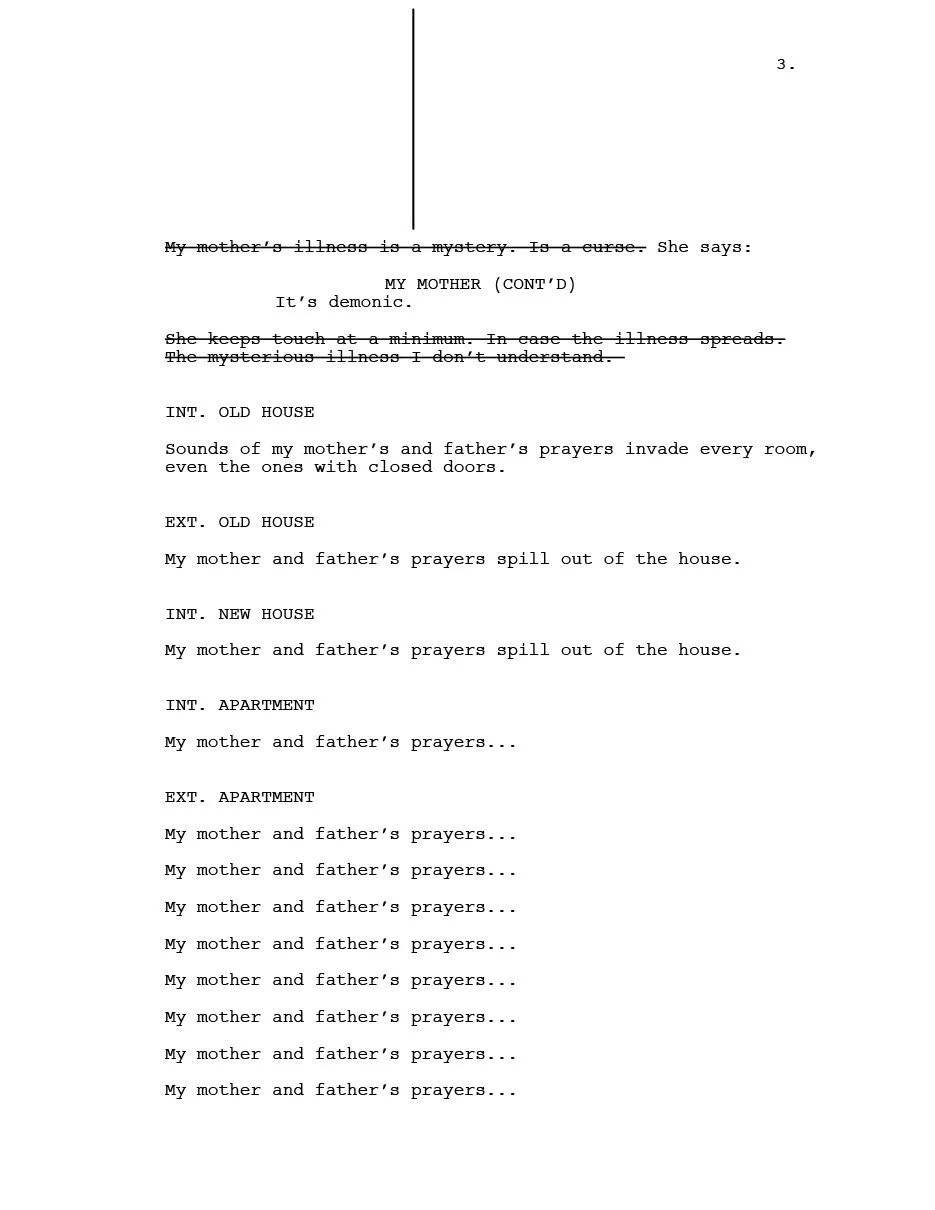

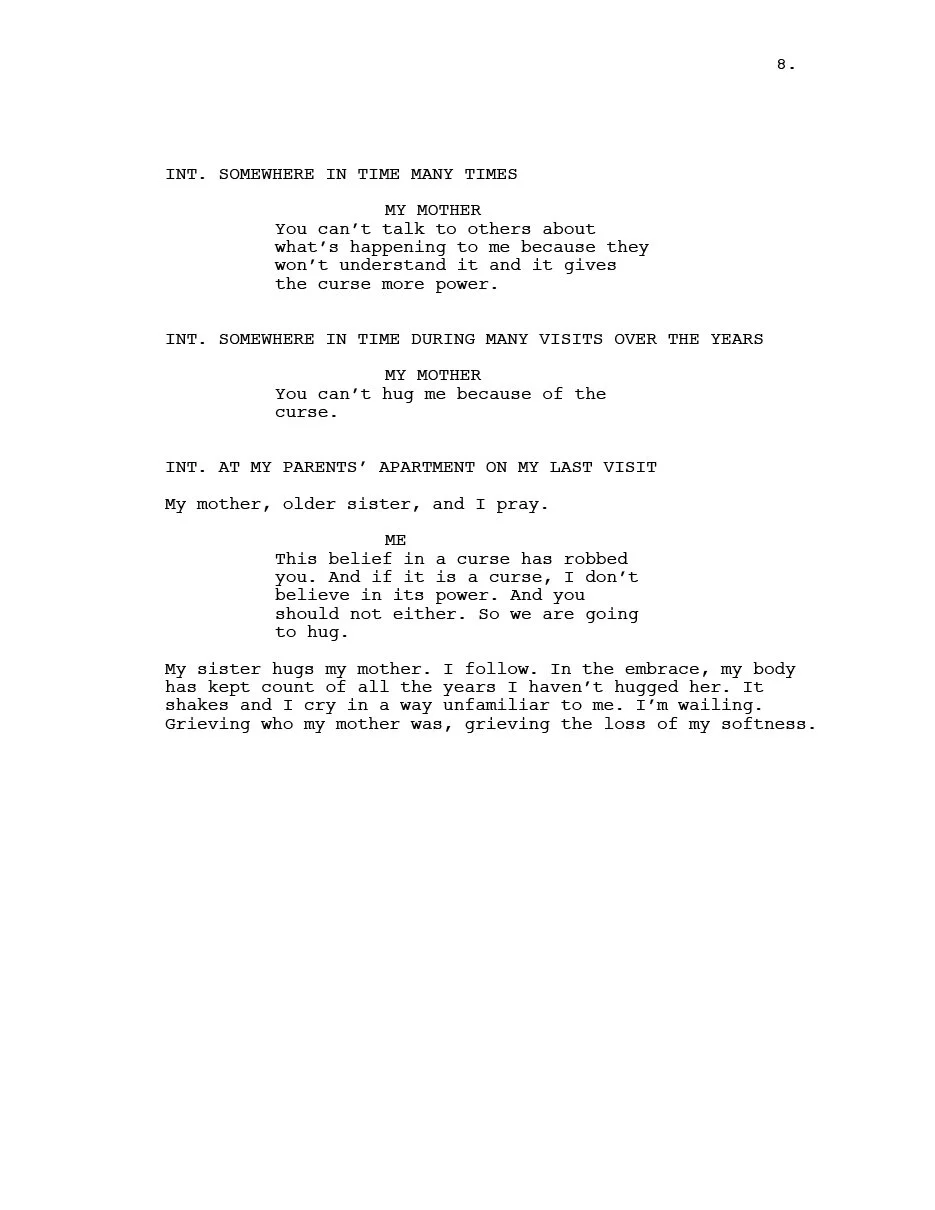

To think that the intimacy of this scene, of a patient anguished from being locked in a room being helped by another who notices him, was produced through a certain non-interventionism of documentary provoked in me a disdain toward the filmmakers. That it takes simply to unlock a door for another to walk out of it and be freed from captivity. Only later in the film is it revealed through the casual dialogue of the patient with his caretakers that he's, presumably, regularly left in there for 35 minutes at a time, perhaps for management's sake. Who knows how often this scene, the tapping of the window and amnesia of most recent events, is repeated or to what effect unlocking a door now will do for later; it's as if the urgency of the tapping is what's most constant, that which "is" here at all. Subtle drama can be crafted at the scale to which moments are noticed, moments small and few amongst the many that are otherwise neglected, lost, ignored.

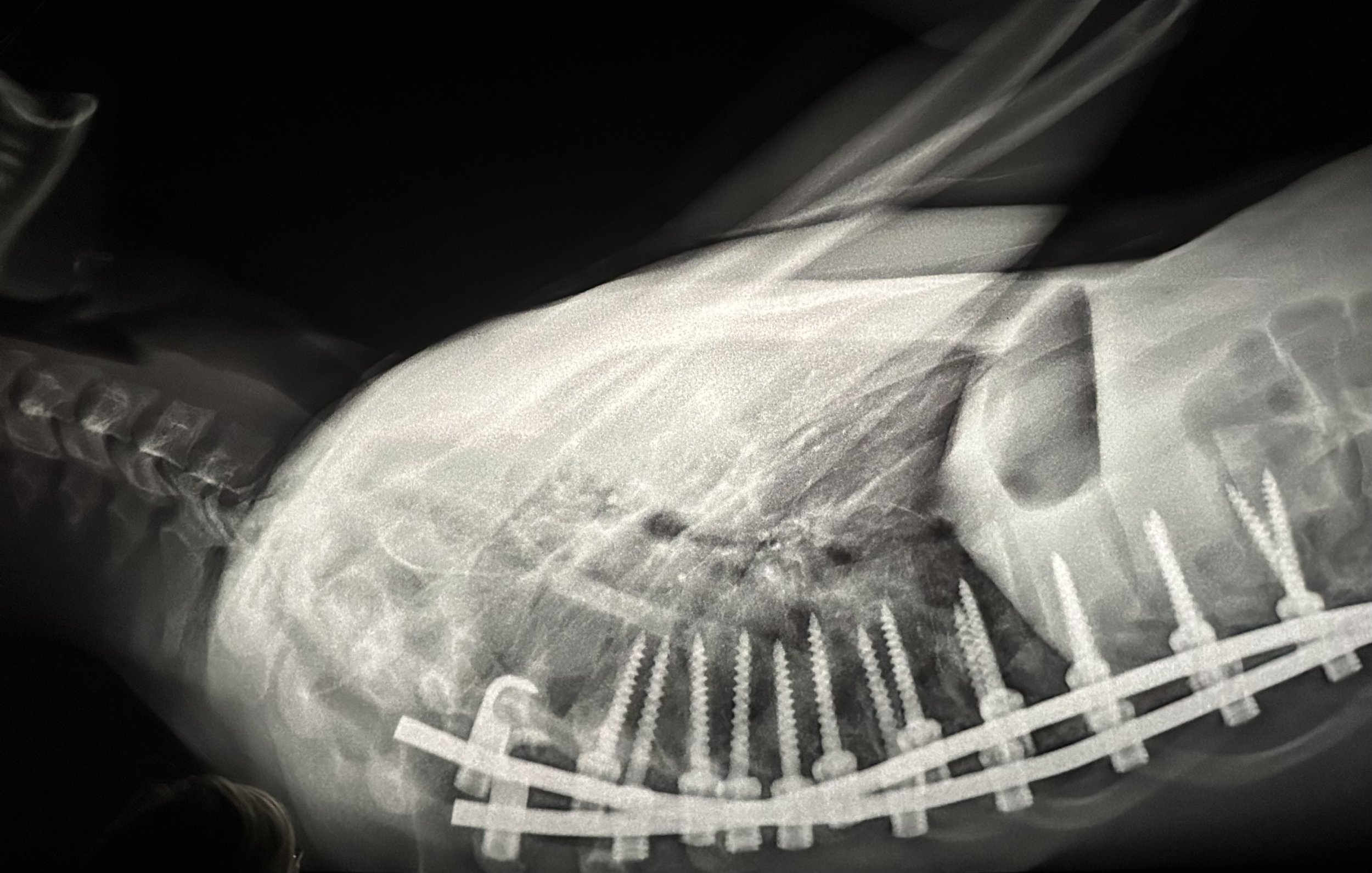

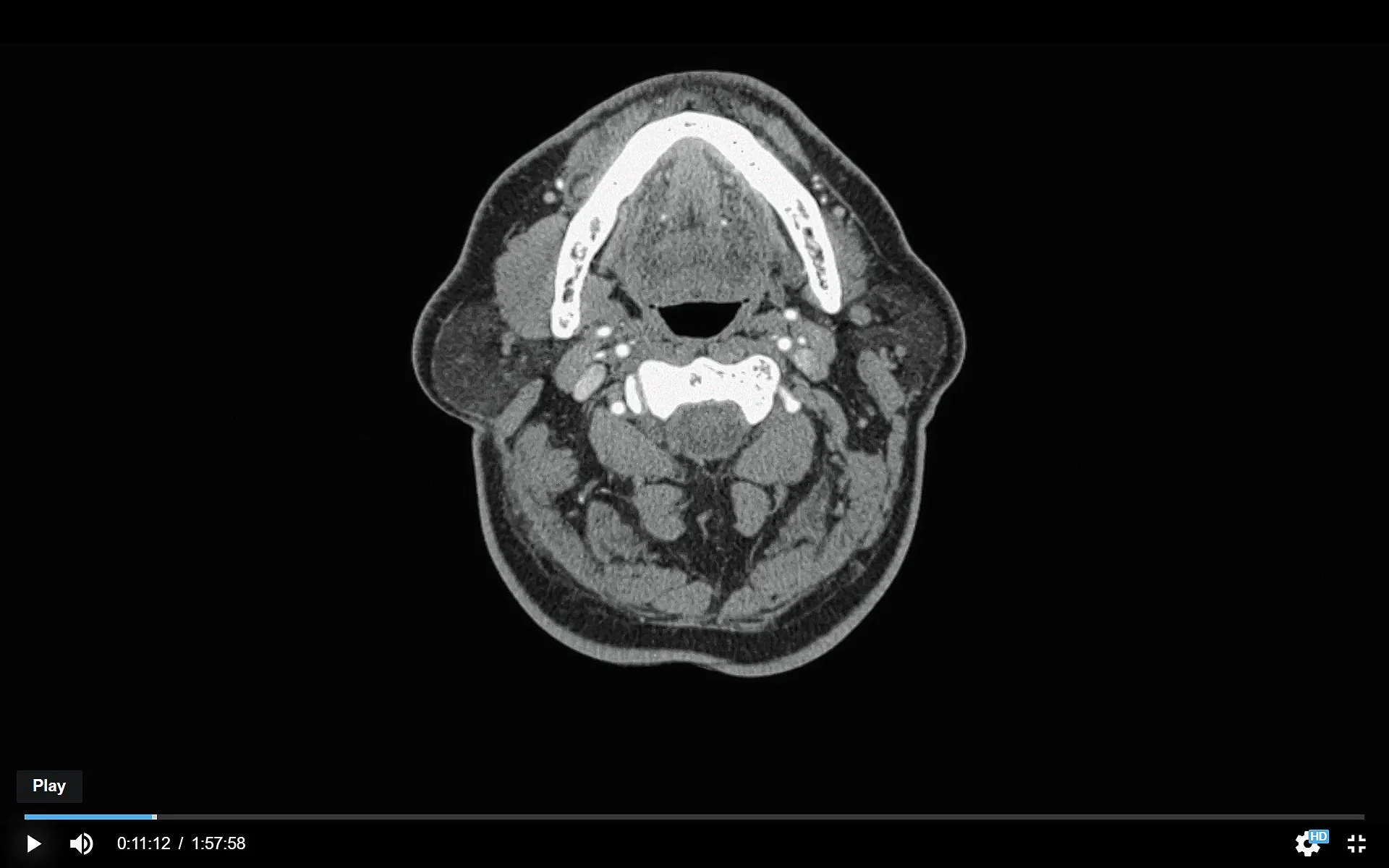

The single shot which is most clearly emblazoned on my memory is the shot of the scalpel cutting open the pregnant woman’s belly for a Cesarean. The doctors pull the opening apart with apparent violence, reaching in to scoop out the baby, who is, thankfully, very small but apparently healthy. The mother indicates that she still has sensation in her belly and feel the pinchers when they touch her, but she makes no sound, so we have no idea what sort of pain she is feeling, or if she is feeling anything at all.

Just a month before this, I watched my own daughter give birth in a Santa Monica hospital. It was a less violent birth, but there was still a lot of tearing, bleeding and cutting, as the placenta did not come out whole but had to be removed surgically, bit by bit. The table behind her (and out of her sight) looked like a butcher’s table or even a slaughterhouse. There were many small bleeding bits arranged all over the bright blue tablecloth.

We saw brief shots of the baby in utero, close enough to see the face, the eyes, the nose. So when she did come out and we were able to witness her first moments of life she was already real to us, in ways that the mother was not.

The doctors in this scene seemed caring and sympathetic, with none of the sarcastic remarks that we heard on the sound track for many of the other procedures. In particular, they wanted to reassure the mother that her baby was safe, although she had been in a dangerous situation a few minutes before.

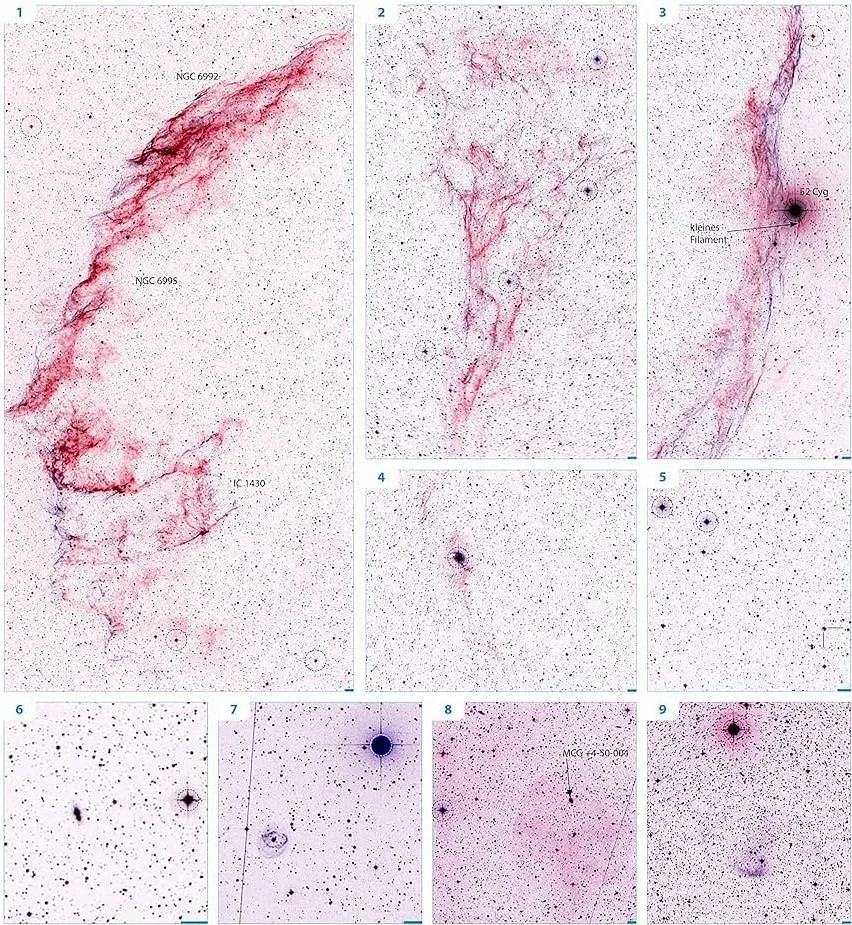

Bodies of light

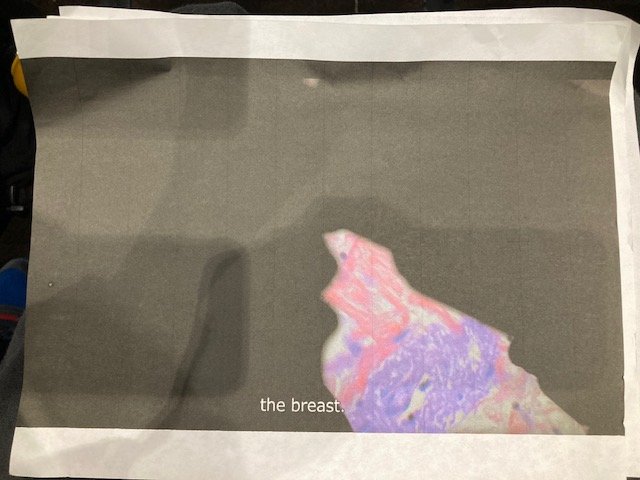

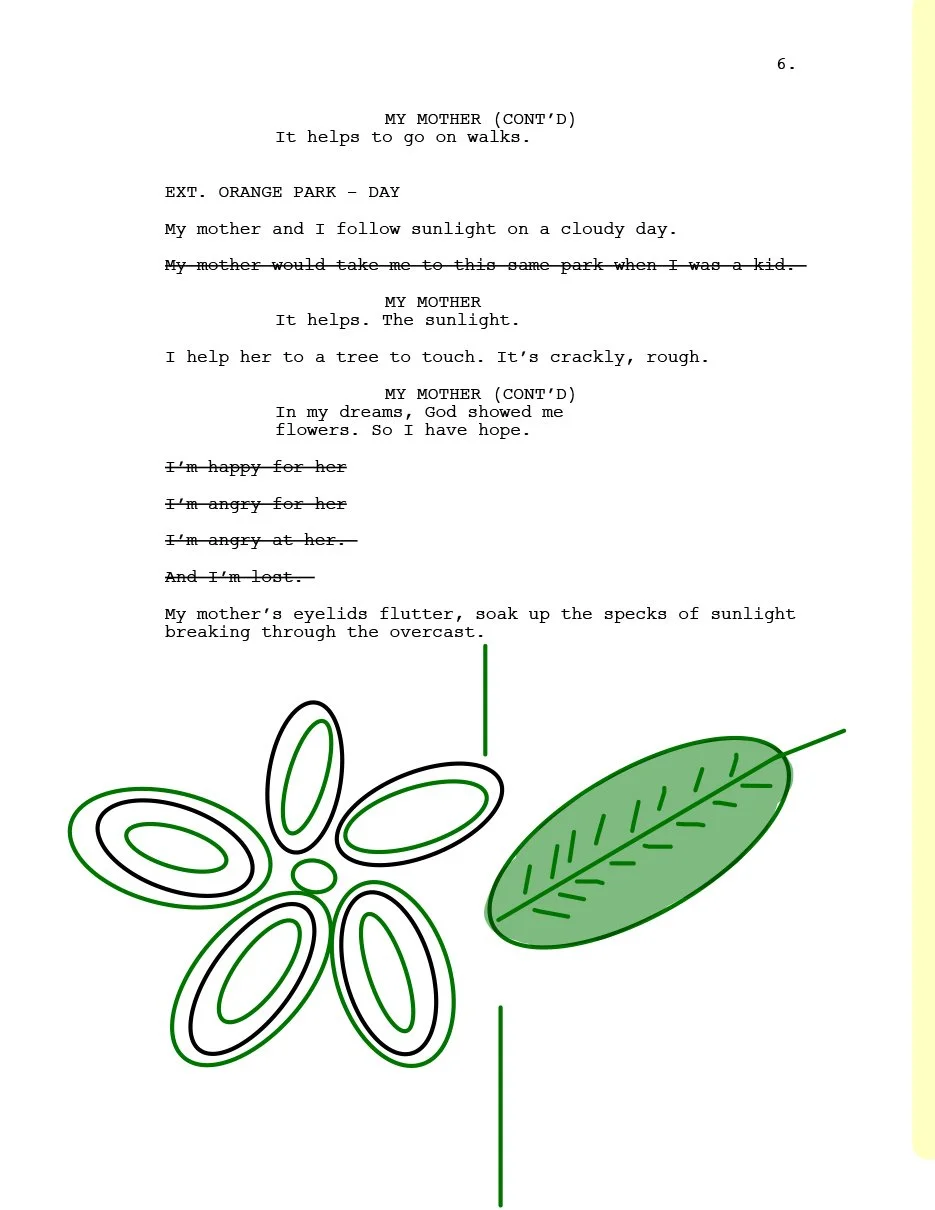

In the Flesh look inside and outside the human body.

Looking inside feels like looking at smaller worlds (cells, tissues, plasma, etc.). These images recall looking outside Earth (galaxies, constellations, stars, etc.)—other cosmic worlds that are also bodies of light—the near and the far within.

Amateur observations of galaxies:

“Small, round, brighter to the middle”

“A small, misty round spot that gradually brightens towards the center”

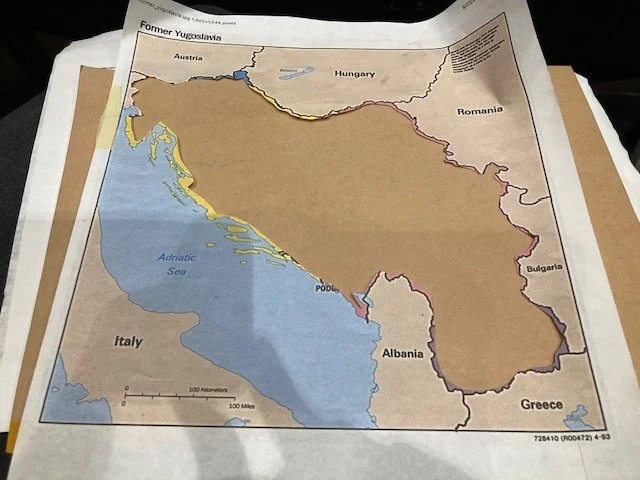

Every time I visit doctors, they inquire about my parents' health. I consistently respond truthfully: my father died from cardiac arrest in his sleep, my great-uncle met the same fate, my grandfather died because of colon cancer after refusing surgery, and another grandfather died because of heart disease during a surgical procedure.

After recounting this, I always follow with an optimistic note: the women in our family tend to live long lives

(and they're all doctors).